Disraeli the Jew and the Empire of the Shopkeepers - Julius Evola

Julius Evola, « Disraeli the Jew and the Empire of the Shopkeepers [L’Ebreo Disraeli e la costruzione dell’impero dei mercanti] », La Vita italiana, trad. Thompkins et Cariou, septembre 1940, p. 253-259.

In a short article published in this journal during the period of the sanctions (November 1935), we tried to explain the nature of the ‘British Empire’ from the point of view of the typology of forms of civilisation.

On that occasion, we showed that it is nothing but a travesty and a contradiction of a real Empire. An Empire worthy of the name is a supra-national organisation based upon heroic, aristocratic, and spiritual values. There is nothing of this sort in the ‘British Empire’. All normal hierarchical relations are on the contrary subjected to a veritable inversion. England possesses a monarchy, an almost feudal nobility, and a military caste which, at least up until very recent years, showed remarkable qualities of character and of sang-froid. But all this is mere appearance. The real centre of the ‘Empire’ is elsewhere; it is, if we may put it this way, within the caste of merchants in the most general sense, of which the modern forms are plutocratic oligarchy, finance, and industrial and commercial monopoly. The ‘Shopkeeper’ is the veritable master of Britain; the unscrupulous and cynical spirit of the merchant, his economic interests, his desire to gain possession to the greatest possible extent of all the world’s riches, these are the bases of English ‘Imperial’ politics, and the real driving forces of English life, beneath the monarchical, conservative appearances.

We know that, wherever economic interests predominate, the Jew rapidly rises and accedes to the commanding positions. The penetration of Judaism into England is not a thing of recent days alone. It was the English Revolution and Protestantism which threw open England’s doors. The Jews, who had been expelled by Edward I in 1290, were readmitted to England as a result of a Petition accepted by Cromwell and finally approved by Charles II in 1649. From this time forward, the Jews, and above all the Spanish Jews (the Sephardim) began to immigrate en masse to England, bringing with them the riches which they had acquired by more or less dubious means, and it was these riches, as we have just explained, which allowed them to accede to the centres of command within English life, to the aristocracy and to positions very close to the Crown. Less than a century after their re-admission, the Jews were so sure of themselves that they demanded to be naturalised, that is to say, to be granted British citizenship. This had a very interesting result: the Law, or Bill, naturalising the Jews was approved in 1740. Most of its supporters were members of the upper classes or high dignitaries within the Protestant Church, which shows us the extent to which these elements had already become Judaised or corrupted by Jewish gold. The reaction came not from the English upper classes, but from the people. The Law of 1740 provoked such outrage and disorder among the populace that it was abrogated in 1753.

The Jews now resorted to another tactic: they abandoned their synagogues and converted, nominally, to Christianity. Thus the obstacle was circumvented and their work of penetration proceeded at an accelerated pace. What mattered to the Jews was to keep their positions of command and to eliminate the religious arguments on which the opposition of that period principally rested; everything else was secondary, since the converted Jew remains, in his instincts, his mentality, and his manner of action, entirely Jewish, as is shown by one striking example among many others: the extremely influential Jewish banker Sampson Gideon, despite having converted, continued to support the Jewish community and was buried in a Jewish cemetery. His money bought for his son an enormous property and the title of Baronet.

This was the preferred tactic of the rich Jews of England from the eighteenth century on: they supplanted the English feudal nobility by acquiring their properties and titles, and thus mixing themselves with the aristocracy, by the nature of the British representative system, they came closer and closer to the government, with the natural consequence of a progressive Judaification of the English political mentality.

In addition, from 1745 to 1749, Sampson Gideon financed the British government from capital which he had multiplied in a dubious manner: by speculating on the Seven Years’ War, more or less as Rothschild did when he made a killing on stocks while only he knew from his own agents the outcome of the battle of Waterloo.

At the same time, in order to increase their influence, the Jews systematically allied themselves to the nobility; the fact that in 1772 it was felt to be necessary to prevent the marriage of members of the British royal family to Jews by means of the Royal Marriages Act, should give us some idea of extent of the Jewish penetration.

By these two means there was brought about a convergence of interests which became more and more apparent between British imperialism and British capitalism, which was itself tied by more and more indissoluble and complex knots to Jewish capitalism.

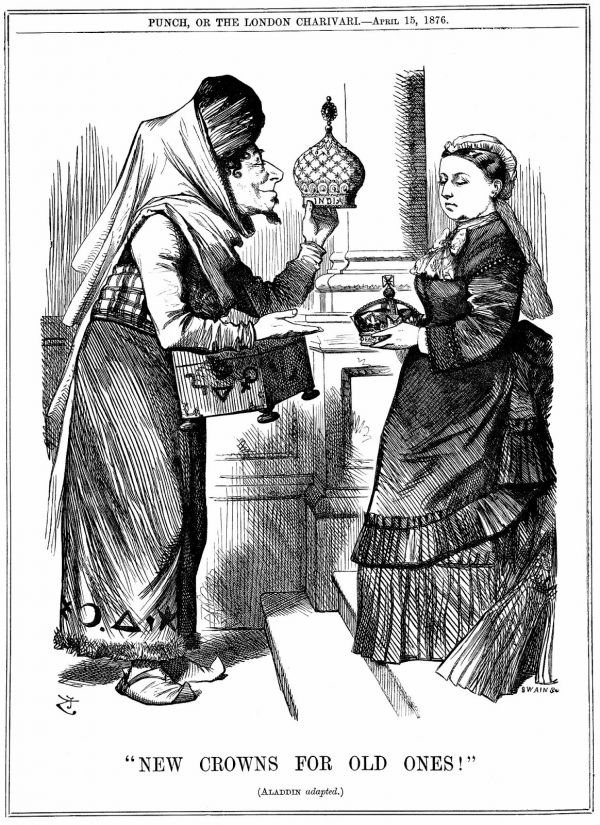

Yet, from the inception of imperialism on the large scale, what was less apparent was that the ‘British Empire’ was a creature of Judaism, which a Jew had given as a present to the British Royal Crown.

This Jew was Benjamin Disraeli, Queen Victoria’s Prime Minister, ennobled under the title Lord Beaconsfield. This development was remarkably interesting. Until that time, it had occurred to no-one to associate with the dignity of Empire an idea of riches like that which attaches to colonial possessions. Even after the Ghibelline Middle Ages, all traditional spirits would have seen this as a real extravagance and a caricature, since the Imperial idea had always had a sacred aura connected to a higher function of domination and civilisation and to a right which was in a certain sense transcendent. Only one Jew could have conceived the idea of ‘reforming’ the conception of Empire and making of it something plutocratic and transforming it into imperialistic materialism. This Jew was Disraeli – ‘Dizzy’ as he was known. It was he who made of Queen Victoria an ‘Empress’, a colonial Empress, the Empress of India. This indefatigable proponent of the English ‘Imperial’ idea modelled his conception upon the Jewish Messianic-imperial idea, the idea of a people whose power consists in the riches of others, over which they take power, and which they cynically exploit and control. Disraeli always attacked very violently those who wished to separate England from her overseas territories, within which, as a Jewish historian has pointed out, Jews were the pioneers. Disraeli knew who it was that sustained this England which in turn was to dominate the riches of the world; it is possible that he was among those initiates who knew that it was more than a simple British-Jewish plutocracy which was pulling the strings. One recalls those often-quoted words of Disraeli: ‘The world is governed by very different personages from what is imagined by those who are not behind the scenes.’

‘What an actor the man is! And yet, the first impression that he gives us is of absolute sincerity. Some think of him as a foreigner. Does England belong to him, or does he belong to England? Is he conservative or liberal? All this doubtless matters not at all to him. The power of Venice, the imperial republic on which the sun never set, this is the vision that fascinates him. England is the Israel of his imagination and if fortune is with him he will be the Prime Minister of the Empire.’

The critic who wrote these words of Disraeli, when he was merely the leader of the Conservative Party, showed himself thereby to have been possessed of a genuine prophetic spirit. His words capture the true spirit of ‘Dizzy’ in action. The reference to Venice, in material terms, derives from the fact that Disraeli’s family, originally from Cento, near Ferrara, had sought its fortunes in Venice before setting off for England; it was also because of his family that Dizzy would have recalled the ‘imperial’ Venetian idea, to the level of which, in strict connection with the Jewish idea, he wished to raise England. There also was found the ‘imperial’ idea of the merchant, of the power of a bourgeois oligarchy built upon gold, commerce, overseas possessions, and trade. All others would serve as means and instruments to this end. But to realise this ‘Venetian’ ideal, given that Venice itself was at least nominally a free republic, it was necessary to rob England of whatever in her organisation had retained the ancient traditional spirit. Here we have another characteristic feature of Disraeli’s activity.

We cannot provide here a profound exposé of the party-political conflicts of England in Disraeli’s time. However, most of our readers will know of the battles between the Tories, the partisans of the monarch, conservative and mostly Catholic, and the Whigs, a Lutheran aristocracy jealous of its independence and favourable to new liberal ideas. Disraeli’s master-stroke was to by-pass to some extent this opposition by becoming the leader of a new party, to be called, in a restricted sense, ‘Conservative’, which would become a powerful enough instrument for the application of his ideas to neutralise whatever was still good in each of these parties by means of the assistance offered by the other. To put this differently, in Disraeli’s ‘Conservative Party’, the true conservatives became liberals and the liberals, conversely, became at least to some extent conservatives, since it was easy to show them by means of the utilitarian ideas which they already possessed that their interests and those of their adversaries coincided. Having thus realised, with his new party, the ‘quid medium’, Disraeli turned England into a simple oligarchical republic. His ‘Conservative Party’ was in reality a sort of clique, held together by common class interests but divided internally, seized with liberalism, and utterly lacking in ideals. Naturally, Jewish and Masonic influences predominated in it.

It seems nevertheless that Disraeli saw even further than this. This becomes apparent from his novel cycle, The New England. Sybil, or The Two Nations reflects exactly the ideological tactic which Freemasonry had already employed to prepare the French Revolution. Disraeli does not conceal his enthusiasm for the lower classes of society, stating that it is they who will create the future when they are guided by their natural leaders, a new enlightened elite which will have surmounted the prejudices of the past. Such ideas enthused the younger generation of the English nobility, which dreamed of playing this leading rôle of new ‘enlightened’ aristocrats, thereby digging their own grave. In the other novel of the same cycle, Coningsby, the central character is a mysterious Jew of Spanish origin, Sidonia – ‘a mixture of Disraeli and Rothschild, or rather, of what Disraeli would have liked to be and what he would have liked Rothschild to be’ (Maurois). This Sidonia transmits to Coningsby, the symbol of the new England, the doctrine of ‘heroic ambition’; here, again, we find the pseudo-conservative ideal of Disraeli. Sidonia’s solution is a government with conservative ideas but liberal practices. In the final analysis, once the English Tory aristocracy had become liberal, and its ideas had become no more than simple ‘principles’ without practical consequences, all that remained was to flatter their ambitions, in order that they should play the rôle of ‘leaders of the people’ – destined, naturally, to be made victims of in the subsequent phase of the subversion, just as had happened to the French aristocrats who had cherished such new ideas. On this subject, in addition to what we find exposed in these books, we should note that it was Disraeli who introduced universal suffrage into Britain, at least in the rudimentary form of the suffrage of all property-owning heads of households, which he skilfully presented as a compromise acceptable to Tories as well as Whigs. But the destructive labours of Disraeli did not confine themselves to politics; they extended also to the domain of religion. It is here that the Jew simply throws away his mask. It was necessary for him to undermine the elements of English society in their most interior foundation, which was the Christian religion, and, above all, the Catholic religion. To this end, Disraeli propounded his famous theory of the convergence and reciprocal integration of Judaism and Catholicism. Here is what he wrote in Sybil: ‘Christianity without Judaism is incomprehensible, in the same way that Judaism without Catholicism is incomplete.’ In Tancred he adds to this, claiming that the task of the Church is to defend, in a materialistic society, the fundamental principles, of Jewish origin, which are found in the two Testaments. This thesis was so extreme that Carlyle declared the ‘Jewish insolence’ of ‘Dizzy’ insupportable, and asked, ‘For how much longer shall John Bull allow this absurd monkey to dance upon his stomach?’

But in the matter of Judaism, Disraeli, who, because he had been baptised, declared himself to be a Christian, was both intransigent and ready for anything. By any and every means, without caring about possible scandal, he maintained the thesis of the alliance between the ‘conservatives’, now weakened in the manner we have discussed, and the Jews. To persecute the Jews would be the gravest error possible for the conservative party to commit, because it would turn them into chiefs of the revolutionary movements. There was also the moral question. ‘You teach your children the history of the Jews’, said Disraeli in his famous speech to the House of Commons, ‘and on your holy days you read at the tops of your voices the exploits of the Jews; on Sundays, if you wish to sing the praises of the Most High or to console yourselves in your misfortunes, you search among the songs of the Jewish poets for an expression of your feelings. In exact proportion to the sincerity of your faith you must accomplish this great act of natural justice . . . as a Christian (?) I will not take the terrible responsibility of excluding those who follow the religion in which my Lord and Saviour was born.’

He could have gone no further in impudence. In fact, this declaration caused a scandal among the ‘conservatives’, but one without consequences. The prudent and noiseless penetration of Jewry into the English upper classes and into the government itself continued. It was Disraeli who performed the coup upon Egypt in 1875 – with whose help? Rothschild. In 1875, the Khedive had financial worries and Disraeli managed to learn that he was willing to sell 177,000 shares of Suez Canal stock. This was a magnificent opportunity to gain certain control of the route to the Indies. The government hesitated. Rothschild did not. Here is the record of the historic conversation between Disraeli and Rothschild (Disraeli had asked him for four million pounds sterling): ‘What guarantee can you offer me?’ ‘The British government.’ ‘You shall have five million tomorrow.’ The interest on the loan was ‘extremely low’; naturally, the real and important interest of the Jewish clique lay on another and less visible plane . . .

Disraeli did not fail to make more convenient to the Jews of England their ritual observance. A little-known fact is that the ‘English Saturday’ is nothing other than the Jewish Sabbath, the ritual day of rest of the Jews. It was suitably Disraeli who introduced it to England, under an adequate social pretext.

Thus, as the Judaification of old feudal England was accomplished by diverse means, and as the old aristocracy gradually decomposed and underwent inoculation with ideas which would make it an easy prey for the material and spiritual influences of Judaism and Freemasonry, Disraeli did not forget his other task, that of augmenting and reinforcing the power of the new ‘Empire of Shopkeepers’, the new ‘Imperial Venice’, the reborn Israel of the Promise. This he did in a manner which was just as characteristically Jewish. Disraeli was one of the principal instigators of that sad and cynical English foreign policy by means of ‘protected’ third parties and the use of blackmail, which it pushes to the most extreme consequences. The most striking case is that of the Russo-Turkish War. Disraeli did not hesitate to betray the ancient cause of European solidarity, by placing Turkey under British protection. Turkey, defeated, was saved by Britain; by use of the well-known ‘English’ method of threats and sanctions, Disraeli was able to paralyse the Slavic advance to the South without a single shot being fired, and a grateful Turkey made him a present of Cyprus. At the Congress of Berlin, the Russian ambassador, Gortshakov, was unable to restrain himself from crying dolorously: ‘To have sacrificed a hundred thousand soldiers and a hundred million of money, and for nothing!’ * There is a factor even more serious, from a higher point of view. By virtue of this situation, brought about by Disraeli, Turkey was admitted into the community of the European nations protected by so-called ‘International Justice’. We say ‘so-called’ because, until that time, far from being held to be valid for all the peoples of the world, this justice was held to be valid uniquely among the group of the European nations; it was a form of recourse and of internal law for Europeans. With the admission of Turkey, a new phase of international law began, and this was truly the phase in which ‘justice’ became a mask and its ‘international’ character became a ruse of ‘democracy’, for it was simply an instrument in the service of Anglo-Jewry, and subsequently of the French also. This development led to the League of Nations, to crisis, and to actual war.

The last years of Disraeli’s life were nevertheless agitated ones. The misdeeds of the plutocracy and the pseudo-conservative cliques began to be felt when they brought about a general financial crisis, agricultural and even colonial, in the Empire of which Disraeli had dreamed and which had become a reality: there followed the Afghan Revolt, the Zulu War, and the prelude to the Boer War. The aged Disraeli, now Lord Beaconsfield and favourite of Queen Victoria, ended up losing his position. He was replaced by Gladstone. In spite of everything, this was a mere changing of the guard. The cabals, the ‘systems’, the directives of international imperialist politics, the false conservatism, the Jewish mentality which more and more destroyed the remains of the old ethic of the gentleman and of fair play in favour of a bottomless hypocrisy and materialism, all this survived and developed, in the form of the ‘British Empire’, from the time of Disraeli onwards, and always retained the mark of its author. Until today.

Tradition requires that each year the merchants of the City of London, home of the Anglo-Jewish plutocracy, invite the Lord Mayor to a banquet and receive the confidences and expressions of trust of the Prime Minister in a speech which he makes at this event. The last speech of this sort that Disraeli gave was another expression of the ‘imperialist’ faith. ‘For the English, to be patriots means to maintain the Empire, and in maintaining the Empire lies their liberty.’ However, one should say that, in the obstinate and hopeless war which England actually conducts, it is the spirit of the Jew Disraeli which lives on. If the English, by following this spirit, bring about the ruin of their ‘Empire’, and of their nation, it is to this champion of the Chosen People that they must be grateful.