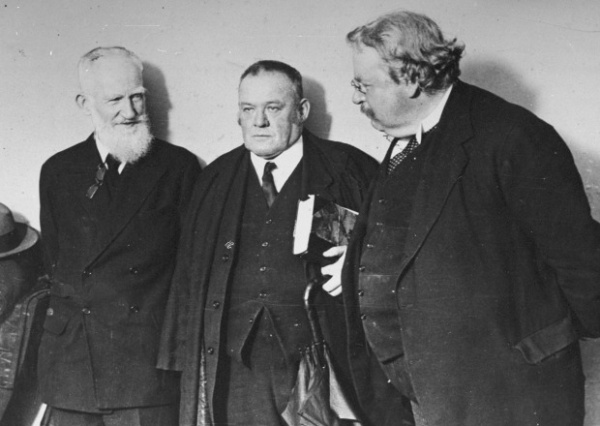

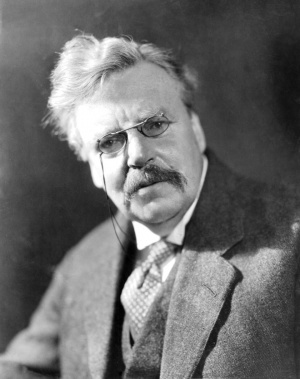

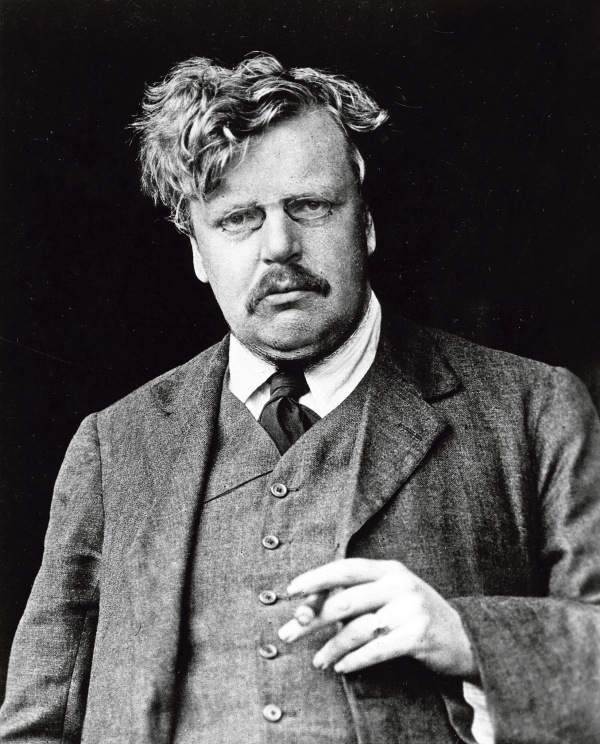

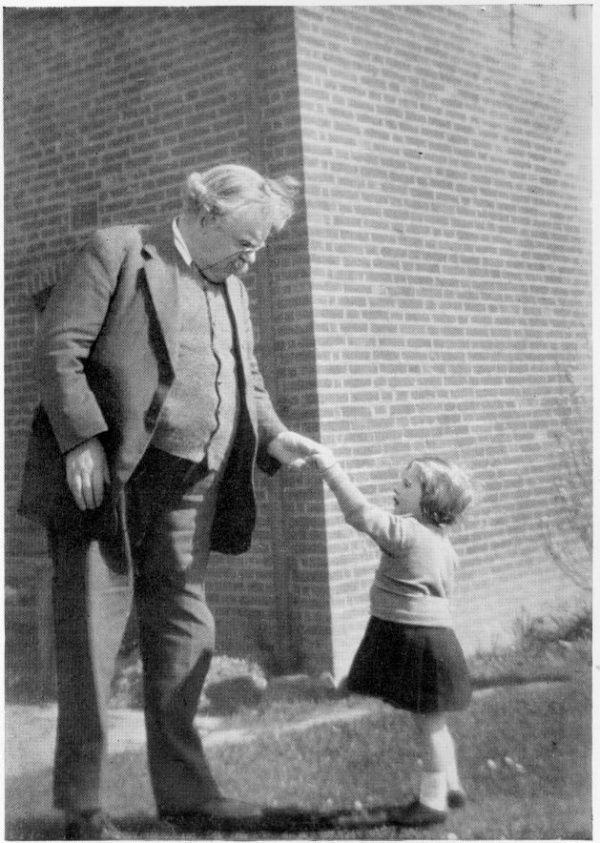

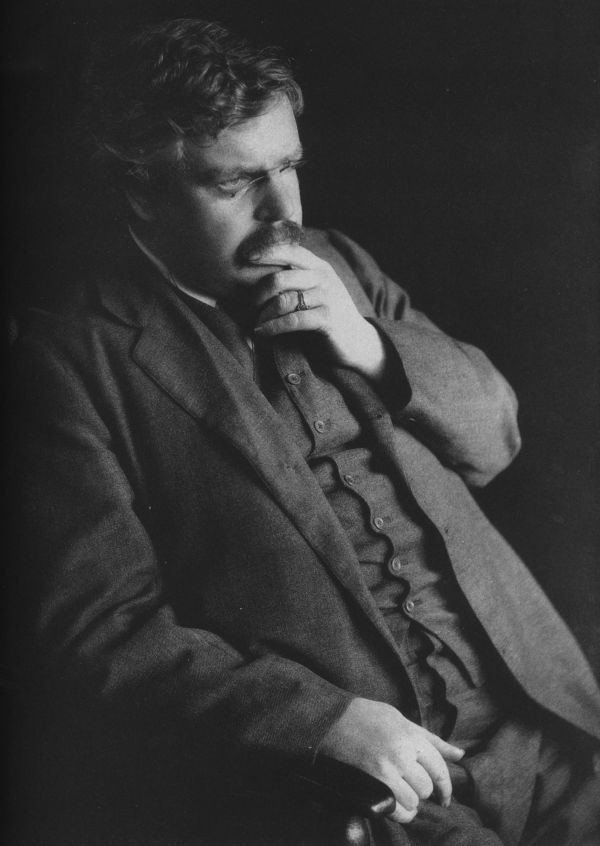

Gilbert Keith Chesterton

Citationes

“All the empires and the kingdoms have failed, because of this inherent and continual weakness, that they were founded by strong men and upon strong men. But this one thing, the historic Christian Church, was founded on a weak man, and for that reason it is indestructible. For no chain is stronger than its weakest link.”

- « Tous les empires et tous les royaumes se sont effondrés à cause de cette faiblesse inhérente et perpétuelle, c’est-à-dire pour avoir été fondés par des hommes forts et sur des hommes forts. Mais cette communauté, l’Église chrétienne, fut fondée sur un homme faible, et c’est pour cette raison qu’elle est indestructible. Car aucune chaîne n’est plus forte que son chaînon le plus faible. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Hérétiques (1905), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220294), p. 62

“There is only one thing in the modern world that has been face to face with Paganism; there is only one thing in the modern world which in that sense knows anything about Paganism: and that is Christianity. That fact is really the weak point in the whole of that hedonistic neo-Paganism of which I have spoken. All that genuinely remains of the ancient hymns or the ancient dances of Europe, all that has honestly come to us from the festivals of Phoebus or Pan, is to be found in the festivals of the Christian Church. If any one wants to hold the end of a chain which really goes back to the heathen mysteries, he had better take hold of a festoon of flowers at Easter or a string of sausages at Christmas. Everything else in the modern world is of Christian origin, even everything that seems most anti-Christian. The French Revolution is of Christian origin. The newspaper is of Christian origin. The anarchists are of Christian origin. Physical science is of Christian origin. The attack on Christianity is of Christian origin. There is one thing, and one thing only, in existence at the present day which can in any sense accurately be said to be of pagan origin, and that is Christianity.”

- « Il y a une seule chose dans le monde moderne qui se soit trouvée face à face avec le paganisme ; il y a une chose dans le monde moderne qui, en ce sens, sache tout du paganisme : c’est le christianisme. Ce fait est en réalité le point faible de tout ce néopaganisme hédoniste dont j’ai parlé. Tout ce qui nous reste d’authentique des anciens hymnes ou des anciennes danses de l’Europe, tout ce qui nous est sincèrement parvenu des fêtes de Phébus ou de Pan, on le retrouve dans les fêtes de l’Église chrétienne. Si quelqu’un veut tenir l’extrémité d’une chaîne qui remonte réellement aux mystères païens, il n’a qu’à saisir une guirlande de fleurs à Pâques ou un chapelet de saucisses à Noël. Tout le reste, dans le monde moderne, est d’origine chrétienne, même ce qui nous semble le plus antichrétien. La Révolution française est d’origine chrétienne. Le journal est d’origine chrétienne. Les anarchistes sont d’origine chrétienne. La science physique est d’origine chrétienne. Les attaques contre le christianisme sont d’origine chrétienne. Il y a une seule chose, et seulement une chose aujourd’hui, dont on puisse dire avec exactitude qu’elle est d’origine païenne dans tous les sens du terme, c’est le christianisme. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Hérétiques (1905), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220294), p. 142

“The modern world is filled with men who hold dogmas so strongly that they do not even know that they are dogmas.”

- « Le monde moderne est rempli d’hommes qui s’accrochent si fortement aux dogmes qu’ils ne savent même pas que ce sont des dogmes. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Hérétiques (1905), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220294), p. 270

"The modern world is not evil; in some ways the modern world is far too good. It is full of wild and wasted virtues. When a religious scheme is shattered (as Christianity was shattered at the Reformation), it is not merely the vices that are let loose. The vices are, indeed, let loose, and they wander and do damage. But the virtues are let loose also; and the virtues wander more wildly, and the virtues do more terrible damage. The modern world is full of the old Christian virtues gone mad. The virtues have gone mad because they have been isolated from each other and are wandering alone. Thus some scientists care for truth; and their truth is pitiless. Thus some humanitarians only care for pity; and their pity (I am sorry to say) is often untruthful."

- « Le monde moderne n’est pas mauvais : à certains égards, il est bien trop bon. Il est rempli de vertus féroces et gâchées. Lorsqu’un dispositif religieux est brisé (comme le fut le christianisme pendant la Réforme), ce ne sont pas seulement les vices qui sont libérés. Les vices sont en effet libérés, et ils errent de par le monde en faisant des ravages ; mais les vertus le sont aussi, et elles errent plus férocement encore en faisant des ravages plus terribles. Le monde moderne est saturé des vieilles vertus chrétiennes virant à la folie. Elles ont viré à la folie parce qu’on les a isolées les unes des autres et qu’elles errent indépendamment dans la solitude. Ainsi des scientifiques se passionnent-ils pour la vérité, et leur vérité est impitoyable. Ainsi des "humanitaires" ne se soucient-ils que de la pitié, mais leur pitié (je regrette de le dire) est souvent mensongère. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 50

“This is why ordinary people have a much more exciting time; while odd people are always complaining of the dulness of life. This is also why the new novels die so quickly, and why the old fairy tales endure for ever. The old fairy tale makes the hero a normal human boy; it is his adventures that are startling; they startle him because he is normal. But in the modern psychological novel the hero is abnormal; the centre is not central. Hence the fiercest adventures fail to affect him adequately, and the book is monotonous. You can make a story out of a hero among dragons; but not out of a dragon among dragons. The fairy tale discusses what a sane man will do in a mad world. The sober realistic novel of to-day discusses what an essential lunatic will do in a dull world.”

- « C’est pourquoi les gens ordinaires s’amusent beaucoup plus, alors que les gens bizarres se plaignent sans cesse de la monotonie de la vie. C’est aussi la raison pour laquelle les romans nouveaux meurent si vite, alors que les contes de fées sont éternels. Dans un conte de fées, le héros est un garçon normal ; ce sont ses aventures qui sont étonnantes, et elles l’étonnent parce qu’il est normal. Dans le roman psychologique moderne, en revanche, le héros est anormal, et le centre n’est pas central. Ainsi les aventures les plus abracadabrantes échouent toujours à l’affecter comme elles le devraient, et le livre est ennuyeux. On peut inventer l’histoire d’un héros entouré de dragons, mais non pas celle d’un dragon entouré de dragons. Le conte de fées envisage ce qu’un homme sain d’esprit ferait dans un monde de fous. Le roman réaliste et prudent d’aujourd’hui envisage ce qu’un homme essentiellement fou ferai dans un monde insignifiant. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 27

“We have not any need to rebel against antiquity; we have to rebel against novelty. It is the new rulers, the capitalist or the editor, who really hold up the modern world. There is no fear that a modern king will attempt to override the constitution; it is more likely that he will ignore the constitution and work behind its back; he will take no advantage of his kingly power; it is more likely that he will take advantage of his kingly powerlessness, of the fact that he is free from criticism and publicity. For the king is the most private person of our time. It will not be necessary for any one to fight again against the proposal of a censorship of the press. We do not need a censorship of the press. We have a censorship by the press.”

- « Nous n’avons aucun besoin de nous rebeller contre l’Antiquité ; il faut nous rebeller contre la nouveauté. Ce sont les nouveaux dirigeants, le capitaliste ou le rédacteur en chef, qui exercent réellement leur emprise sur le monde moderne. Il n’y a pas lieu de craindre qu’un roi ne tente aujourd’hui d’outrepasser la Constitution : il est plus probable qu’il l’ignorera pour agir en cachette ; il ne profitera nullement de son pouvoir royal ; il est plus probable qu’il profitera de son impuissance royal, du fait qu’elle le soustrait à la critique et à la publicité. Car le roi est la personne la moins publique de notre époque. Personne ne se trouvera dans la nécessité de lutter encore une fois contre un projet de censure de la presse. Nous n’avons pas besoin d’une censure de la presse. Nous avons une censure par la presse. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 184

“I have always maintained that men were naturally backsliders; that human virtue tended of its own nature to rust or to rot; I have always said that human beings as such go wrong, especially happy human beings, especially proud and prosperous human beings. This eternal revolution, this suspicion sustained through centuries, you (being a vague modern) call the doctrine of progress. If you were a philosopher you would call it, as I do, the doctrine of original sin. You may call it the cosmic advance as much as you like; I call it what it is — the Fall.”

- « J’ai toujours soutenu que les hommes étaient naturellement des récidivistes ; que la vertu humaine tendait, de par sa nature, à se rouiller ou à pourrir ; j’ai toujours dit que les êtres humains comme tels deviennent mauvais, surtout les heureux, les orgueilleux et les prospères. Cette révolution éternelle, cette suspicion maintenue à travers les siècles, vous l’appelez (en vague moderne) la doctrine du progrès. Si vous étiez philosophe, vous l’appeleriez, comme je le fais, la doctrine du péché originel. Vous pouvez l’appeler progrès cosmique autant que vous voudrez ; je l’appelle par ce qu’elle est : la Chute. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 185

"Tradition means giving votes to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about."

- « On pourrait définir la tradition comme une extension du droit de vote au passé. Elle consiste à accorder le droit de suffrage à la plus obscure de toutes les classes, celle de nos ancêtres. C’est la démocratie des morts. La tradition refuse de se soumettre à la petite oligarchie arrogante de ceux qui ne font que se trouver par hasard sur terre. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 76-77

“Obviously, it will not do to take our ideal from the principle in nature; for the simple reason that (except for some human or divine theory), there is no principle in nature. For instance, the cheap anti-democrat of to-day will tell you solemnly that there is no equality in nature. He is right, but he does not see the logical addendum. There is no equality in nature; also there is no inequality in nature. Inequality, as much as equality, implies a standard of value. To read aristocracy into the anarchy of animals is just as sentimental as to read democracy into it. Both aristocracy and democracy are human ideals: the one saying that all men are valuable, the other that some men are more valuable.”

- « Bien entendu, il ne conviendrait pas de tirer notre idéal du principe dans la nature, pour la simple raison qu’il n’y a pas de principe dans la nature (hormis pour quelque théorie humaine ou divine). Par exemple, le misérable antidémocrate d’aujourd’hui vous dira solennellement que dans la nature l’égalité n’existe pas. Il a raison, mais il n’en voit pas le corollaire logique. Il y a pas d’égalité dans la nature, mais il n’y a pas non plus d’inégalité dans la nature. L’inégalité, comme l’égalité, implique une échelle de valeurs. Voir une aristocratie dans l’anarchie des animaux relève tout autant du sentimentalisme que d’y voir une démocratie. L’aristocratie et la démocratie sont toutes deux des idéaux humains, l’une affirmant que tous les hommes sont d’une même valeur, l’autre que certains hommes ont plus de valeur que d’autres. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 164-165

“Almost every contemporary proposal to bring freedom into the church is simply a proposal to bring tyranny into the world.”

- « Presque toutes les tentatives contemporaines pour introduire la liberté dans l’Église ne sont que des tentatives pour introduire la tyrannie dans le monde. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 199

“[...] there are men who will ruin themselves and ruin their civilization if they may ruin also this old fantastic tale. [...] Men who begin to fight the Church for the sake of freedom and humanity end by flinging away freedom and humanity if only they may fight the Church.”

- « [...] il est des hommes qui se détruiraient et détruiraient leur civilisation s’ils pouvaient du même coup détruire ce vieux conte fantastique. [...] Les hommes qui se mettent à combattre l’Église au nom de la liberté et de l’humanité finissent par liquider liberté et humanité pourvu qu’ils puissent combattre l’Église. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 221

“The secularists have not wrecked divine things; but the secularists have wrecked secular things, if that is any comfort to them. The Titans did not scale heaven; but they laid waste the world.”

- « Les laïcs n’ont pas ravagé les choses divines ; ils ont ravagé les choses profanes, si cela peut les consoler. Les Titans n’on pas escaladé le ciel, mais ils ont saccagé le monde. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Orthodoxie (1908), trad. Lucien d’Azay, éd. Flammarion, coll. « Climats », 2010 (ISBN 9782081220287), p. 223

"[...] [Feminism] is mixed up with a muddled idea that women are free when they serve their employers but slaves when they help their husbands [...].

- « Le féminisme pense que les femmes sont libres lorsqu’elles servent leurs employeurs, mais esclaves lorsqu’elles aident leurs maris. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Social Reform versus Birth Control (1927)

"It is the only thing that frees a man from the degrading slavery of being a child of his age."

- « C’est la seule religion qui affranchit un homme de la servitude dégradante d’être un enfant de son temps. »

- — Gilbert Keith Chesterton, « La raison pour laquelle je suis devenu catholique (1926) », dans L’Église catholique et la conversion, trad. Gérard Joulie, éd. L’Homme Nouveau, 2010 (ISBN 9782915988352), p.