Différences entre les versions de « The Bruges Speech - Margaret Thatcher »

| Ligne 24 : | Ligne 24 : | ||

And the first book to be printed in the English language was produced here in Bruges by William Caxton . | And the first book to be printed in the English language was produced here in Bruges by William Caxton . | ||

| − | + | {{Center|Margaret Thatcher|}} | |

== Britain and Europe == | == Britain and Europe == | ||

| Ligne 93 : | Ligne 93 : | ||

Nor should we forget that European values have helped to make the United States of America into the valiant defender of freedom which she has become. | Nor should we forget that European values have helped to make the United States of America into the valiant defender of freedom which she has become. | ||

| − | |||

== Europe's future == | == Europe's future == | ||

Version du 27 août 2015 à 07:00

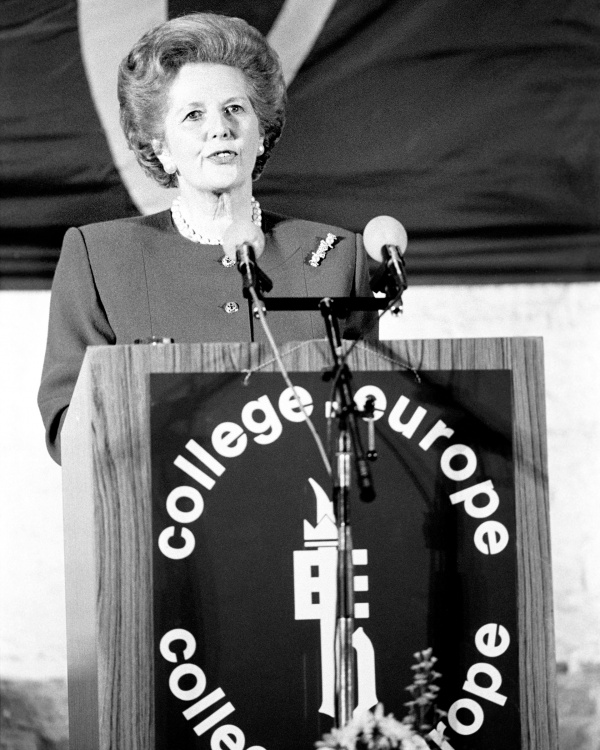

Speech to the College of Europe, September 20 1988 by Margaret Thatcher at Bruges.

Introduction

Prime Minister

Prime Minister, Rector, Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen:

First, may I thank you for giving me the opportunity to return to Bruges and in very different circumstances from my last visit shortly after the Zeebrugge Ferry disaster, when Belgian courage and the devotion of your doctors and nurses saved so many British lives.

And second, may I say what a pleasure it is to speak at the College of Europe under the distinguished leadership of its [Professor Lukaszewski ] Rector.

The College plays a vital and increasingly important part in the life of the European Community.

And third, may I also thank you for inviting me to deliver my address in this magnificent hall.

What better place to speak of Europe's future than a building which so gloriously recalls the greatness that Europe had already achieved over 600 years ago.

Your city of Bruges has many other historical associations for us in Britain. Geoffrey Chaucer was a frequent visitor here.

And the first book to be printed in the English language was produced here in Bruges by William Caxton .

Britain and Europe

Mr. Chairman, you have invited me to speak on the subject of Britain and Europe. Perhaps I should congratulate you on your courage.

If you believe some of the things said and written about my views on Europe, it must seem rather like inviting Genghis Khan to speak on the virtues of peaceful coexistence!

I want to start by disposing of some myths about my country, Britain, and its relationship with Europe and to do that, I must say something about the identity of Europe itself.

Europe is not the creation of the Treaty of Rome.

Nor is the European idea the property of any group or institution.

We British are as much heirs to the legacy of European culture as any other nation. Our links to the rest of Europe, the continent of Europe, have been the dominant factor in our history.

For three hundred years, we were part of the Roman Empire and our maps still trace the straight lines of the roads the Romans built.

Our ancestors—Celts, Saxons, Danes—came from the Continent.

Our nation was—in that favourite Community word—"restructured" under the Norman and Angevin rule in the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

This year, we celebrate the three hundredth anniversary of the glorious revolution in which the British crown passed to Prince William of Orange and Queen Mary.

Visit the great churches and cathedrals of Britain, read our literature and listen to our language: all bear witness to the cultural riches which we have drawn from Europe and other Europeans from us.

We in Britain are rightly proud of the way in which, since Magna Carta in the year 1215, we have pioneered and developed representative institutions to stand as bastions of freedom.

And proud too of the way in which for centuries Britain was a home for people from the rest of Europe who sought sanctuary from tyranny.

But we know that without the European legacy of political ideas we could not have achieved as much as we did.

From classical and mediaeval thought we have borrowed that concept of the rule of law which marks out a civilised society from barbarism.

And on that idea of Christendom, to which the Rector referred—Christendom for long synonymous with Europe—with its recognition of the unique and spiritual nature of the individual, on that idea, we still base our belief in personal liberty and other human rights.

Too often, the history of Europe is described as a series of interminable wars and quarrels.

Yet from our perspective today surely what strikes us most is our common experience. For instance, the story of how Europeans explored and colonised—and yes, without apology—civilised much of the world is an extraordinary tale of talent, skill and courage.

But we British have in a very special way contributed to Europe.

Over the centuries we have fought to prevent Europe from falling under the dominance of a single power.

We have fought and we have died for her freedom.

Only miles from here, in Belgium, lie the bodies of 120,000 British soldiers who died in the First World War.

Had it not been for that willingness to fight and to die, Europe would have been united long before now—but not in liberty, not in justice.

It was British support to resistance movements throughout the last War that helped to keep alive the flame of liberty in so many countries until the day of liberation.

Tomorrow, King Baudouin will attend a service in Brussels to commemorate the many brave Belgians who gave their lives in service with the Royal Air Force—a sacrifice which we shall never forget.

And it was from our island fortress that the liberation of Europe itself was mounted.

And still, today, we stand together.

Nearly 70,000 British servicemen are stationed on the mainland of Europe.

All these things alone are proof of our commitment to Europe's future.

The European Community is one manifestation of that European identity, but it is not the only one.

We must never forget that east of the Iron Curtain, people who once enjoyed a full share of European culture, freedom and identity have been cut off from their roots.

We shall always look on Warsaw, Prague and Budapest as great European cities.

Nor should we forget that European values have helped to make the United States of America into the valiant defender of freedom which she has become.

Europe's future

This is no arid chronicle of obscure facts from the dust-filled libraries of history.

It is the record of nearly two thousand years of British involvement in Europe, cooperation with Europe and contribution to Europe, contribution which today is as valid and as strong as ever [sic].

Yes, we have looked also to wider horizons—as have others—and thank goodness for that, because Europe never would have prospered and never will prosper as a narrow-minded, inward-looking club.

The European Community belongs to all its members.

It must reflect the traditions and aspirations of all its members.

And let me be quite clear.

Britain does not dream of some cosy, isolated existence on the fringes of the European Community. Our destiny is in Europe, as part of the Community.

That is not to say that our future lies only in Europe, but nor does that of France or Spain or, indeed, of any other member.

The Community is not an end in itself.

Nor is it an institutional device to be constantly modified according to the dictates of some abstract intellectual concept.

Nor must it be ossified by endless regulation.

The European Community is a practical means by which Europe can ensure the future prosperity and security of its people in a world in which there are many other powerful nations and groups of nations.

We Europeans cannot afford to waste our energies on internal disputes or arcane institutional debates.

They are no substitute for effective action.

Europe has to be ready both to contribute in full measure to its own security and to compete commercially and industrially in a world in which success goes to the countries which encourage individual initiative and enterprise, rather than those which attempt to diminish them.

This evening I want to set out some guiding principles for the future which I believe will ensure that Europe does succeed, not just in economic and defence terms but also in the quality of life and the influence of its peoples.[fo 3]

Willing cooperation between sovereign states

My first guiding principle is this: willing and active cooperation between independent sovereign states is the best way to build a successful European Community.

To try to suppress nationhood and concentrate power at the centre of a European conglomerate would be highly damaging and would jeopardise the objectives we seek to achieve.

Europe will be stronger precisely because it has France as France, Spain as Spain, Britain as Britain, each with its own customs, traditions and identity. It would be folly to try to fit them into some sort of identikit European personality.

Some of the founding fathers of the Community thought that the United States of America might be its model.

But the whole history of America is quite different from Europe.

People went there to get away from the intolerance and constraints of life in Europe.

They sought liberty and opportunity; and their strong sense of purpose has, over two centuries, helped to create a new unity and pride in being American, just as our pride lies in being British or Belgian or Dutch or German.

I am the first to say that on many great issues the countries of Europe should try to speak with a single voice.

I want to see us work more closely on the things we can do better together than alone.

Europe is stronger when we do so, whether it be in trade, in defence or in our relations with the rest of the world.

But working more closely together does not require power to be centralised in Brussels or decisions to be taken by an appointed bureaucracy.

Indeed, it is ironic that just when those countries such as the Soviet Union, which have tried to run everything from the centre, are learning that success depends on dispersing power and decisions away from the centre, there are some in the Community who seem to want to move in the opposite direction.

We have not successfully rolled back the frontiers of the state in Britain, only to see them re-imposed at a European level with a European super-state exercising a new dominance from Brussels.

Certainly we want to see Europe more united and with a greater sense of common purpose.

But it must be in a way which preserves the different traditions, parliamentary powers and sense of national pride in one's own country; for these have been the source of Europe's vitality through the centuries.

Encouraging change

My second guiding principle is this: Community policies must tackle present problems in a practical way, however difficult that may be.

If we cannot reform those Community policies which are patently wrong or ineffective and which are rightly causing public disquiet, then we shall not get the public support for the Community's future development.

And that is why the achievements of the European Council in Brussels last February are so important.

It was not right that half the total Community budget was being spent on storing and disposing of surplus food.

Now those stocks are being sharply reduced.

It was absolutely right to decide that agriculture's share of the budget should be cut in order to free resources for other policies, such as helping the less well-off regions and helping training for jobs.

It was right too to introduce tighter budgetary discipline to enforce these decisions and to bring the Community spending under better control.

And those who complained that the Community was spending so much time on financial detail missed the point. You cannot build on unsound foundations, financial or otherwise, and it was the fundamental reforms agreed last winter which paved the way for the remarkable progress which we have made since on the Single Market.

But we cannot rest on what we have achieved to date.

For example, the task of reforming the Common Agricultural Policy is far from complete.

Certainly, Europe needs a stable and efficient farming industry.

But the CAP has become unwieldy, inefficient and grossly expensive. Production of unwanted surpluses safeguards neither the income nor the future of farmers themselves.

We must continue to pursue policies which relate supply more closely to market requirements, and which will reduce over-production and limit costs.

Of course, we must protect the villages and rural areas which are such an important part of our national life, but not by the instrument of agricultural prices.

Tackling these problems requires political courage.

The Community will only damage itself in the eyes of its own people and the outside world if that courage is lacking.

Europe open to enterprise

My third guiding principle is the need for Community policies which encourage enterprise.

If Europe is to flourish and create the jobs of the future, enterprise is the key.

The basic framework is there: the Treaty of Rome itself was intended as a Charter for Economic Liberty.

But that it is not how it has always been read, still less applied.

The lesson of the economic history of Europe in the 70's and 80's is that central planning and detailed control do not work and that personal endeavour and initiative do.

That a State-controlled economy is a recipe for low growth and that free enterprise within a framework of law brings better results.

The aim of a Europe open to enterprise is the moving force behind the creation of the Single European Market in 1992. By getting rid of barriers, by making it possible for companies to operate on a European scale, we can best compete with the United States, Japan and other new economic powers emerging in Asia and elsewhere.[fo 5]

And that means action to free markets, action to widen choice, action to reduce government intervention.

Our aim should not be more and more detailed regulation from the centre: it should be to deregulate and to remove the constraints on trade.

Britain has been in the lead in opening its markets to others.

The City of London has long welcomed financial institutions from all over the world, which is why it is the biggest and most successful financial centre in Europe.

We have opened our market for telecommunications equipment, introduced competition into the market services and even into the network itself—steps which others in Europe are only now beginning to face.

In air transport, we have taken the lead in liberalisation and seen the benefits in cheaper fares and wider choice.

Our coastal shipping trade is open to the merchant navies of Europe.

We wish we could say the same of many other Community members.

Regarding monetary matters, let me say this. The key issue is not whether there should be a European Central Bank.

The immediate and practical requirements are:

- to implement the Community's commitment to free movement of capital—in Britain, we have it;

- and to the abolition through the Community of exchange controls—in Britain, we abolished them in 1979;

- to establish a genuinely free market in financial services in banking, insurance, investment;

- and to make greater use of the ecu.

This autumn, Britain is issuing ecu-denominated Treasury bills and hopes to see other Community governments increasingly do the same.

These are the real requirements because they are what the Community business and industry need if they are to compete effectively in the wider world.

And they are what the European consumer wants, for they will widen his choice and lower his costs.

It is to such basic practical steps that the Community's attention should be devoted.

When those have been achieved and sustained over a period of time, we shall be in a better position to judge the next move.

It is the same with frontiers between our countries.

Of course, we want to make it easier for goods to pass through frontiers.

Of course, we must make it easier for people to travel throughout the Community.

But it is a matter of plain common sense that we cannot totally abolish frontier controls if we are also to protect our citizens from crime and stop the movement of drugs, of terrorists and of illegal immigrants.[fo 6]

That was underlined graphically only three weeks ago when one brave German customs officer, doing his duty on the frontier between Holland and Germany, struck a major blow against the terrorists of the IRA.

And before I leave the subject of a single market, may I say that we certainly do not need new regulations which raise the cost of employment and make Europe's labour market less flexible and less competitive with overseas suppliers.

If we are to have a European Company Statute, it should contain the minimum regulations.

And certainly we in Britain would fight attempts to introduce collectivism and corporatism at the European level—although what people wish to do in their own countries is a matter for them.

Europe open to the world

My fourth guiding principle is that Europe should not be protectionist.

The expansion of the world economy requires us to continue the process of removing barriers to trade, and to do so in the multilateral negotiations in the GATT.

It would be a betrayal if, while breaking down constraints on trade within Europe, the Community were to erect greater external protection.

We must ensure that our approach to world trade is consistent with the liberalisation we preach at home.

We have a responsibility to give a lead on this, a responsibility which is particularly directed towards the less developed countries.

They need not only aid; more than anything, they need improved trading opportunities if they are to gain the dignity of growing economic strength and independence.

Europe and defence

My last guiding principle concerns the most fundamental issue—the European countries' role in defence.

Europe must continue to maintain a sure defence through NATO.

There can be no question of relaxing our efforts, even though it means taking difficult decisions and meeting heavy costs.

It is to NATO that we owe the peace that has been maintained over 40 years.

The fact is things are going our way: the democratic model of a free enterprise society has proved itself superior; freedom is on the offensive, a peaceful offensive the world over, for the first time in my life-time.

We must strive to maintain the United States' commitment to Europe's defence. And that means recognising the burden on their resources of the world role they undertake and their point that their allies should bear the full part of the defence of freedom, particularly as Europe grows wealthier.

Increasingly, they will look to Europe to play a part in out-of-area defence, as we have recently done in the Gulf.

NATO and the Western European Union have long recognised where the problems of Europe's defence lie, and have pointed out the solutions. And the time has come when we must give substance to our declarations about a strong defence effort with better value for money.

It is not an institutional problem.

It is not a problem of drafting. It is something at once simpler and more profound: it is a question of political will and political courage, of convincing people in all our countries that we cannot rely for ever on others for our defence, but that each member of the Alliance must shoulder a fair share of the burden.

We must keep up public support for nuclear deterrence, remembering that obsolete weapons do not deter, hence the need for modernisation.

We must meet the requirements for effective conventional defence in Europe against Soviet forces which are constantly being modernised.

We should develop the WEU, not as an alternative to NATO, but as a means of strengthening Europe's contribution to the common defence of the West.

Above all, at a time of change and uncertainly in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, we must preserve Europe's unity and resolve so that whatever may happen, our defence is sure.

At the same time, we must negotiate on arms control and keep the door wide open to cooperation on all the other issues covered by the Helsinki Accords.

But let us never forget that our way of life, our vision and all we hope to achieve, is secured not by the rightness of our cause but by the strength of our defence.

On this, we must never falter, never fail.

The British approach

Mr. Chairman, I believe it is not enough just to talk in general terms about a European vision or ideal.

If we believe in it, we must chart the way ahead and identify the next steps.

And that is what I have tried to do this evening.

This approach does not require new documents: they are all there, the North Atlantic Treaty, the Revised Brussels Treaty and the Treaty of Rome, texts written by far-sighted men, a remarkable Belgian— Paul Henri Spaak —among them.

However far we may want to go, the truth is that we can only get there one step at a time.

And what we need now is to take decisions on the next steps forward, rather than let ourselves be distracted by Utopian goals.

Utopia never comes, because we know we should not like it if it did.

Let Europe be a family of nations, understanding each other better, appreciating each other more, doing more together but relishing our national identity no less than our common European endeavour.

Let us have a Europe which plays its full part in the wider world, which looks outward not inward, and which preserves that Atlantic community—that Europe on both sides of the Atlantic—which is our noblest inheritance and our greatest strength.

May I thank you for the privilege of delivering this lecture in this great hall to this great college (applause).